Olympic games we no longer play

Many aspects of the ancient Olympic Games would be perfectly familiar to fans at the upcoming games in Rio de Janeiro: elite international competition, cheering crowds in the tens of thousands, events like sprints, wrestling, discus, and javelin.

Then as now, Olympic contenders often spent years training with expert coaches, and victors were showered with praise and wealth.

But other elements of the ancient games would seem very strange to spectators today.

It’s hard to imagine a modern Olympics featuring the sacrifice of 100 oxen, or the public whipping of athletes caught cheating, or a race in full body armor.

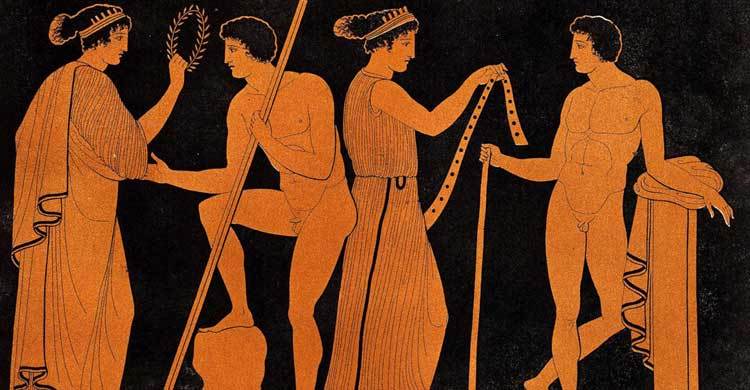

Athletes competed au naturel, examined the entrails of sacrificed animals to see if they prophesied victory, and were rewarded only for winning an event. (There were no prizes for second or third place.)

Despite a clear thread of continuity between the ancient and modern games, the profound influence of warfare and religion on the original Olympics created a spectacle that in many ways would be unrecognizable to modern audiences.

Prowess in Battle and Sport

The first recorded Olympics was held in 776 B.C. at the site of Olympia in the Western Peloponnese.

They likely developed from the practice of holding funeral games to honor fallen warriors and local heroes, though some myths made the Greek demigod Heracles the founder of the games.

They continued without interruption once every four years for almost 1,200 years. They were abolished in A.D. 393 by the Emperor Theodosius, a Christian who saw the worship of Zeus throughout the games as a pagan abomination.

The practice of warfare in the ancient world inspired many Olympic events.

A mass of soldiers running in full armor, for example, was an effective way to surprise and terrify enemy armies. (The Greek historian Herodotus describes the Greek army advancing at a run toward the Persians at the battle of Marathon, a tactic the eastern invaders had apparently never encountered before.)

In the hoplitodromia, or race in armor, a field of 25 athletes ran two lengths of the 210-yard-long (192-meter-long) stadium at Olympia wearing bronze greaves and helmets and lugging shields that may have weighed 30 pounds.

Contestants in the target javelin event hurled javelins at a shield fixed to a pole while galloping on horseback, a standard military practice documented by the historian Xenophon.

Chariot races with teams of two and four horses were incredibly dangerous and popular events.

War chariots were used in Greece since at least the time of Mycenaean civilization, roughly 1600 to 1100 B.C., and the four-horse chariot race was one of the oldest events in the games, first introduced at Olympia in 680 B.C. Only the wealthy could afford the expense of maintaining horses and a chariot. And while the owners of chariots claimed the glory of any victories, they generally hired charioteers to face the risks of competition for them. Crashes were common, spectacular, and often deadly, with the most dangerous moment usually coming at the narrow turns at each end of the stadium.

One famous charioteer was the Roman Emperor Nero, who in A.D. 67 competed in the chariot race at Olympia.

It was hardly a fair contest. Nero entered the four-horse race with a team of 10 horses. He was thrown from his chariot and was unable to complete the race, but he was proclaimed the champion on the grounds that he would have won had he finished the race.

What the Greeks called ‘heavy’ events were also closely connected to combat. Boxing, wrestling, and a combination of the two called pankration all rewarded strength and tactical cunning.

Boxers wore thin gloves made of leather thongs and fought on the open ground, which made it impossible to corner an opponent and extended the length of fights.

If a bout dragged on for hours, the boxers could agree to exchange undefended blows - a pugilistic equivalent of sudden death.

In at least one case, sudden death was exactly what resulted.

The Greek geographer Pausanias tells the story of a fight between Damoxenos and Kreugas that ended when the former jabbed the latter with outstretched fingers, piercing the skin and ripping out his entrails.

Wrestling and pankration could also be brutal. Wrestlers had to throw their opponent to the ground three times to win.

Because there were no weight classes, the largest wrestlers had a distinct advantage. In pankration everything but biting and gouging was allowed.

One fighter, nicknamed ‘Mr. Fingertips,’ was known for breaking an opponent’s fingers at the start of the match to force immediate submission. Another fighter would twist his opponents’ ankles from their sockets.

Despite all of their martial overtones, the ancient games promoted at least temporary peace between the frequently warring Greek city-states.

An inscription on a bronze tablet known as the Sacred Truce guaranteed safe passage for athletes traveling to and from the games and prohibited participating states from engaging in hostilities during the duration of the Olympics.

Because some athletes in the fifth century and after traveled from as far away as North Africa, Asia Minor, Western Spain, and the Black Sea, this truce was ultimately extended to a period of three months. Violators paid a fine of silver to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.

The king of the Greek gods was also honored by lavish sacrifices of oxen and dedicatory statues. By the second century A.D., the pile of accumulated ash from centuries of sacrifices stood 23 feet (seven meters) tall.

On the opening day of the games, athletes swore an oath before Zeus, ‘Keeper of Oaths.’ The brothers, fathers, and trainers of the athletes took the oath as well, promising to uphold all the rules and guaranteeing that they had been training for at least 10 months.

But cheating was an irresistible temptation for some. Dishonest wrestlers rubbed themselves with olive oil so they could slide from their opponent’s grasp.

Bribing judges or even fellow competitors were other documented methods of cheating.

Those caught were publicly whipped and fined, and their shame was immortalized on inscribed statues lining the route athletes walked to enter the stadium.

Like many aspects of the ancient games, this custom is in no danger of being revived by the International Olympic Committee.