Walking a tightrope: Balancing modernity, heritage in Old Dhaka

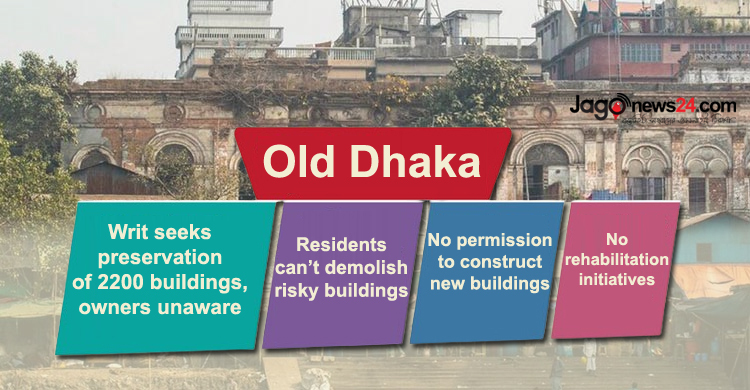

Old Dhaka, a cityscape of historical grandeur and cultural vibrancy, is grappling with a growing crisis. Approximately 2,200 buildings deemed to have archaeological importance are now at the centre of a legal and logistical impasse. Owners cannot demolish or renovate these structures due to a High Court order aimed at preserving their heritage. Yet, these crumbling edifices pose significant risks to residents, many of whom live in precarious conditions with little hope of relief.

Legal limbo over heritage conservation

In 2018, the Urban Study Group (USG), an organisation advocating for the preservation of Old Dhaka’s architectural legacy, filed a writ petition in the High Court. The court subsequently directed the Department of Archaeology to assess these buildings and prevent any changes until a final report was submitted.

However, six years later, the Department of Archaeology has yet to finalise a comprehensive list of heritage structures, citing logistical challenges. “We have inspected about 400 buildings, but only a handful—10 to 12—are suitable for preservation,” said Taimur Islam, CEO of USG.

The delay has left building owners in a state of uncertainty. “We don’t know which houses are protected or if there are any legal barriers to demolition,” said one homeowner, reflecting a sentiment shared widely across Old Dhaka.

Clash between heritage and modernity

The court order was meant to protect Old Dhaka’s rich architectural heritage, including colonial-era structures with intricate Neo-Classical designs. However, many residents and building owners argue that the lack of clear communication and compensation from authorities has made their lives unbearable.

Suman Chakraborty, whose family owns an old one-story house on Dinanath Sen Road, recently attempted to demolish the building to construct a safer structure. He was stopped midway by police, RAJUK (Rajdhani Unnayan Kartipakkha, the capital’s urban development authority), and the Department of Archaeology.

“We didn’t receive any prior notice or letter. The demolition was halted at the final stage, and now we have no place to live,” he said, adding that the house was not listed as a protected structure.

For many, these legal complications are a significant burden. “Most of these buildings are in such poor condition that living in them is dangerous,” said Narayan Chandra, a resident of Shankhari Bazar.

“Yet, we’re stuck because of this writ. The government isn’t offering any compensation or relocation support.”

Risky living amid decay

Shankhari Bazar, one of Old Dhaka’s most iconic streets, is a poignant example of the crisis. Over 50 buildings here are included in the USG’s writ list, leaving their owners unable to renovate or rebuild.

The condition of these structures is dire, with many at risk of collapse. “These buildings lack proper living facilities and are incredibly unsafe,” Chandra noted. Residents are left to endure the precarious conditions with no clear solution in sight.

Authorities acknowledge challenges, but progress remains slow

The Department of Archaeology has admitted to delays in finalising the list of heritage structures. “We began drafting a list in 2013 but faced numerous obstacles in identifying and documenting the buildings,” said Afroza Khan Mita, Regional Director of the Department of Archaeology.

A meeting with stakeholders in June brought some progress, with officials promising to finalise the list by the end of this year. However, many remain skeptical.

USG’s Taimur Islam criticised the lack of urgency. “The court asked for quarterly progress updates, but this hasn’t been done regularly. The Department of Archaeology even suggested it might take another decade to complete the work,” he said.

Call for action

Urban planners and preservationists agree that a balance must be struck between heritage conservation and residents’ safety. Experts suggest that preserving Old Dhaka’s architectural legacy should not come at the expense of public safety or quality of life.

“Buildings are an integral part of our heritage, but so are the people who live in them,” said Islam.

The way forward involves clear communication with homeowners, swift completion of the heritage list, and government support for relocation or rehabilitation. Without these measures, Old Dhaka’s rich history risks being overshadowed by its residents' daily struggles to survive.

For now, the streets of Old Dhaka remain a testament to the complexity of preserving the past while living in the present—a challenge that continues to test the city’s resilience.