New York City to close public schools again

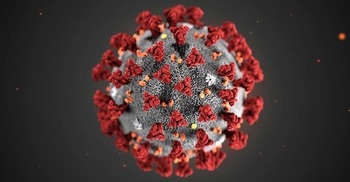

New York City’s entire public school system will close Thursday, signaling that a second wave of the coronavirus has arrived as the city is still struggling to revive from its devastating spring, when it was a global epicenter of the pandemic.

The shutdown was prompted by the city’s reaching a 3% test positivity rate over a seven-day rolling average, the most conservative threshold of any big school district in the country. Schools in the nation’s largest system, with 1.1 million students and 1,800 schools, have been open for in-person instruction for just under eight weeks.

It was a major disappointment for Mayor Bill de Blasio, who was the first big-city mayor in the country to reopen school buildings. Moving to all-remote instruction will disrupt the education of many of the roughly 300,000 children who have been attending in-person classes and create child care problems for parents who count on their children being at school for at least part of the week.

“Today is a tough day, but this is a temporary situation,” de Blasio said on Wednesday in a news conference that had been delayed for five hours amid frantic caucusing by the mayor, governor and union leaders. He declared that “our schools will be back,” but added that reopening might not take place until next month or later.

The closure pointed to the start of an alarming new phase of the city’s battle against the coronavirus, and the mayor and Gov. Andrew Cuomo both indicated Wednesday that further restrictions to public life “were coming, and coming soon,” as de Blasio put it. Limited indoor dining and gyms have been open for under two months.

The return of schoolchildren to classrooms had been a ray of normalcy in a dark time for the city, with theaters still shut, many offices vacant and the mass transit system facing the threat of deep service cuts if federal aid does not arrive soon.

Over the summer, New York had maintained a low virus transmission rate that was the envy of the nation — and its rate is still much lower than the nation’s worst-hit regions. But the city has struggled recently to tamp down the surge that is spiraling out of control across so much of the country, particularly the Midwest and Mountain states.

Though it was clear for at least a week that the city was quickly approaching the dreaded 3% threshold, the actual delivery of the expected news seemed to devolve into disarray on Wednesday.

De Blasio delayed his daily news conference from 10 a.m. until 3 p.m. after he and his aides spent the morning scrambling to ensure that the governor was informed about their plan to close schools. And because the average positivity rate came in at exactly 3%, top city officials went over the math several times to make sure it was accurate.

At a contentious news conference earlier in the afternoon, Cuomo began to shout at reporters who asked whether the schools would be open Thursday and declined to answer the question until a reporter mentioned a New York Times report about the impending closure.

The midafternoon announcement sparked deep frustration among city parents who for months have had little certainty about whether schools would be open and were left with just a few hours to make child care arrangements for Thursday morning.

The timing of the announcement also drew derisive statements from city officials, including the public advocate, Jumaane Williams. “People are scared and stressed, and need plans and assurances,” he said. “Today, we have only executives governing by haphazard tweets and combative press conferences, from City Hall and the State Capitol to the White House.”

Virus transmission in city schools had remained very low since classrooms reopened at the end of September, and the spike in cases does not appear to be caused by the opening of school buildings.

“Our schools have opened and have been remarkably safe,” schools chancellor Richard Carranza said Wednesday.

Still, the city is choosing to end in-person learning while the state is allowing indoor dining and gyms to remain open at reduced capacity. Nonessential workers are also continuing to use public transportation to commute to offices.

That dynamic has infuriated parents run ragged by fluctuating school schedules and has frustrated public health experts who have been pushing for more in-person instruction. It has also led to calls for the mayor and Cuomo to make keeping classrooms open their highest priority.

Across much of Western Europe, bars, restaurants and theaters are closed while elementary schools at least have remained open. De Blasio has said that indoor dining should be reassessed; only Cuomo has the authority to close indoor dining rooms.

The city’s public school families, the vast majority of whom are low-income and Black or Latino, have endured roughly eight months of confusion about whether and when schools would be open or closed.

De Blasio had put school reopening at the center of his push to revive the city, and he has repeatedly said that remote learning is inferior to classroom instruction. But many teachers and parents have said that the city has not done nearly enough to improve online learning.

The mayor has said that closures will be temporary, but cautioned that schools would not automatically reopen the moment that the seven-day positivity rate dipped below 3% again.

He said it would be too disruptive for children and educators to toggle between open and closed schools every few days, suggesting he would wait until community spread of the virus had stabilized at a lower rate.

The mayor said Wednesday that he and Cuomo had spent much of the morning discussing how to safely reopen schools. The two men have agreed that there will be much more testing of students and staff members when schools do reopen, and the mayor said he will require all students to have a permission slip allowing them to be tested in their school buildings.

The mayor and the teachers union, the United Federation of Teachers, have faced intense criticism as the 3% closure threshold drew nearer.

De Blasio has said repeatedly that the union had not pressured him to set the threshold; instead, he called the metric a “social contract” during a recent radio interview, arguing that it was a symbol of how seriously the city had approached school safety.

The mayor set the 3% threshold over the summer, when average positivity rates were hovering around 1% or below. City officials said the number was agreed upon by the mayor’s public health team as part of a package of safety measures that they set out to make the strictest in the world.

In an interview last week, Michael Mulgrew, the union’s president, said he thought the 3% threshold was sound.

He cited warnings from experts that even if there was low transmission in schools, infection could still spread into them from the broader community, increasing the likelihood that students and staff members might carry the virus into their homes and neighborhoods.

Mulgrew said he was dismayed that schools were closing so soon and asserted that expressions of frustration about a shutdown from some New Yorkers seemed hypocritical.

“We had a lot of criticism from people when we were opening schools,” he said. “They didn’t want them open. A lot of that came from the very same people who are yelling now that they want them open.”

He also called on New Yorkers to take the virus seriously in order to drive down numbers again. “If we want to keep our schools open, it’s up to everyone else” to take precautions, Mulgrew said.

In a stroke of bad timing, New York said last month that families had only until this past Sunday to decide if they wanted their children to return to in-person classes at all, most likely until at least next September. Parents have had to make that decision while knowing that schools could close at any moment.

Students who opted back into classroom instruction were set to restart classes between Nov. 30 and Dec. 7. They will now have to wait weeks longer to return to school buildings.

Source: Indian Express/New York Times