NZ mosque shootings hit tight-knit Bangladesh community hard

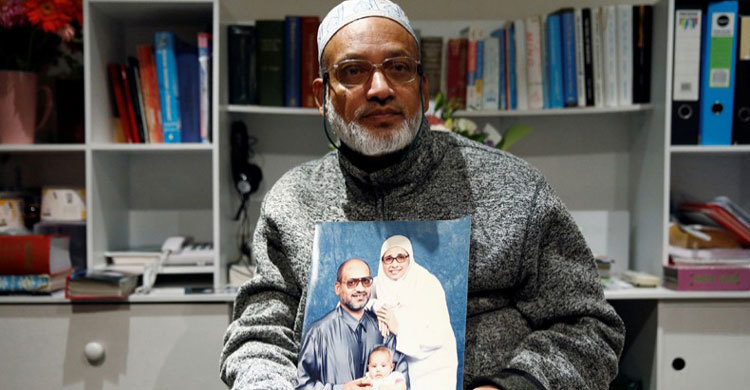

Husna Ahmed was 19 when she arrived in New Zealand from Bangladesh on her wedding day. Waiting to meet her was Farid, the man she would marry in a few hours, as their families had agreed.

A quarter of a century later, the life they had built together was torn apart at the Al Noor mosque in Christchurch when a gunman walked into the building, firing on worshippers at Friday prayers, Reuters reported.

Husna encountered the gunman on his way out of the mosque. He shot her on the footpath. She fell and he fired two more shots, killing her instantly.

Farid, who uses a wheelchair after an earlier accident, was talking to a friend and was delayed from joining worshippers at his usual spot at the front of the mosque, instead praying in a small side room.

He managed to escape when he heard the shooting begin, returning when the gunman left, to find many of his friends and community members dead and comfort those who were dying.

Farid found out about his wife’s death when a detective he knew called his niece as they waited outside the mosque.

She passed the phone: “I don’t want you to wait the whole night, Farid. Go home, she will not come,” Farid said the detective told him.

“At the moment I hear that, my response was I felt numb,” Farid told Reuters. “I had tears but I didn’t break down.” His niece crumbled.

A total of 50 people were killed in the rampage, with as many wounded, as the gunman went from Al Noor to another mosque in the South Island city.

Most victims were migrants or refugees from countries including Pakistan, India, Malaysia, Syria, Turkey, Somalia and Afghanistan.

Husna was one of five members of a growing but tight-knit Bangladeshi community killed, according to the Bangladesh consul in New Zealand, Shafiqur Rahman Bhuiyan. Four others were wounded, one critically, he added.

Members of the Bangladesh cricket team, in town for a test match against New Zealand, narrowly avoided the carnage, turning up at the Al Noor mosque soon after the attack took place.

Based on what eyewitnesses told him, Farid said instead of hiding, Husna helped women and children inside the mosque and ran to the front of the building to look for him.

“She’s such a person who always put other people first and she was even not afraid to give her life saving other people,” Farid said.

Australian Brenton Tarrant, 28, a suspected white supremacist, has been charged with murder. He entered no plea and police said he is likely to face more charges.

The slaughter has rocked Christchurch, and New Zealand, to its core, blanketing the city in grief and driving Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern to promise swift gun law reform.

Farid said he had forgiven his wife’s killer.

“I want to give the message to the person who did this, or if he has any friends who also think like this: I still love you,” Farid said. “I want to hug you and I want to tell him in face that I am talking from my heart. I have no grudge against you, I never hated you, I will never hate you.”

LIKE A MOTHER

A few hours after the massacre as evening fell, the front room of Farid’s home in a sleepy Christchurch suburb where he runs a homeopathy business was full with survivors and friends grieving for a woman many described as like a mother to them.

Husna was born on 12 October in 1974 in Sylhet, a city on the banks the Surma River, in northeastern Bangladesh. She was so fast that Shahzalal Junior High School would only let her run three races, to give her rivals a chance, Farid said.

She moved to New Zealand in 1994.

Thin, nervous and overwhelmed by leaving everyone she knew for a new life in an alien country, she burst into tears when her husband-to-be picked her up from Auckland airport.

He comforted her on the long drive back to Nelson, where he was living, and where she quickly found her feet.

With almost no other Bangladeshis in the small city, Husna made English-speaking friends and learned the language within six months. Farid said she spoke it with more of a Kiwi accent than he did.

When Farid’s workmates at a meatpacking plant agreed to work half an hour longer on Fridays so he could take a break to pray, she cooked them a feast every week in thanks.

And when Farid was partially paralyzed after being run over by a car outside his house, after four years of marriage, she moved with him to Christchurch and became his nurse.

“Our hobby was we used to talk to each other. A lot. And we never felt bored,” he said.

REBUILDING CHRISTCHURCH

When Christchurch was razed by a deadly earthquake in 2011, Husna helped settle an influx of Bangladeshi migrants - qualified engineers, metalworkers and builders - who came to assist the rebuilding of the shattered city.

Mohammad Omar Faruk, 36, was one of the new arrivals. Faruk was working as a welder in Singapore but leapt at the opportunity to come to New Zealand where working conditions were better and permanent residency was possible.

Faruk was also killed at Al Noor mosque.

His employer, Rob van Peer, said he had allowed his team to leave early last Friday after they finished a job by lunchtime, meaning Faruk could attend Friday prayers.

Van Peer said Faruk was loved by his colleagues for his loyal and friendly personality and fast, precise welds.

Zakaria Bhuiyan, a welder at another engineering firm, also died. Newly married, he was waiting for a visitor visa so his wife could travel from Bangladesh.

Mojammel Haque worked as a dentist in Bangladesh and was studying in New Zealand for an advanced medical qualification when he was killed.

All three men knew Husna, said Mojibur Rahman, a welder and former flatmate of Faruk.

“It’s really hard because we are a little community but everyone’s living here in unity, we know each other, we share everything with each together,” he said. “Now I don’t know what’s going to happen, how we become normal.”

The fifth Bangladeshi victim was Abus Samad, 66, a former faculty member of Bangladesh Agriculture University who had been teaching at Christchurch’s Lincoln University.

CUSTOMS AND CARE

Many new workers to Christchurch brought young families, or were starting them and Husna took it upon herself to care for women through their pregnancies, often waking Farid at all hours so he could drive her to the births.

“We think she’s like a mother…if there’s something we needed, we go to Husna,” said Mohammed Jahangir Alan, another welder.

Husna guided his wife, then 19, to a midwife and a doctor and joined her in the delivery room as she gave birth to a baby girl, Alan said.

A few days later Husna shaved the infant’s head, an Islamic ritual which she did for dozens of children in the community. She was so gentle the baby fell asleep while she pulled the razor over the soft skin.

Husna would also lead the customary washing and prayer ritual for women who died. She was due to lead a workshop the day after her death to teach other women the process.

Now, Husna’s devastated female family members will wash her for her funeral, expected later this week.

“We know she would just want us to be a part of it, to wash her,” said her sister-in-law Ayesha Corner.

After the burial, Farid says he wants to continue the work he and his wife used to do and to care for their 15-year-old daughter.

When the lockdown at her school lifted on Friday, their daughter returned home, knowing only her mother was missing and asking where she was.

“I didn’t miss a second, I said: ‘She is with God,’” Farid said.

“She said: ‘You are lying’. She said: ‘Are you telling me I don’t have a mother?’”

“I said: ‘Yes, but I am your mother now and I am your father...we have to change the roles.”