Why Buster Keaton is today's most influential actor

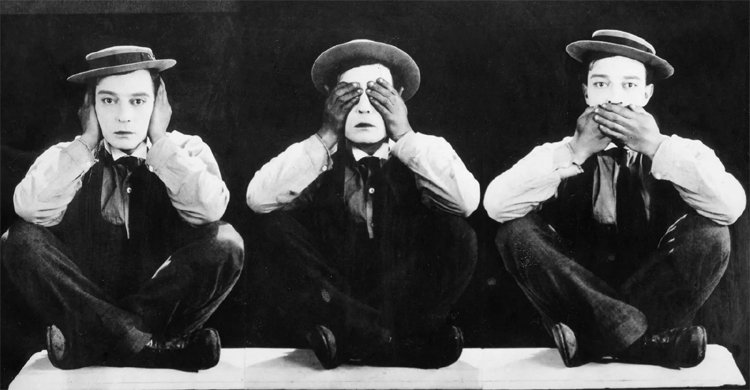

Buster Keaton was something of an enigma to his own era. The silent-film star launched himself between rooftops, battled storms and sand dunes, boarded moving vehicles – and frequently trailed behind them, perfectly horizontal and as suspended as our disbelief – all in the name of comedy, and all while seeming unfazed. Film historian Peter Kramer, in his essay The Makings of a Comic Star, contends that Keaton's "deadpan performance was seen as a highly inappropriate response to the task of creating characters which were rounded and believable". His unrelenting imperturbability was misinterpreted as a lack of emotional expression, or perhaps acting skill.

Nowadays we applaud performances that exhibit this level of restraint, wowed by microscopic gestures that hint at subtext, but refuse to spell it out. As Slate's movie critic and author Dana Stevens points out in Camera Man, a new biography-meets-cultural-history about Buster Keaton and the birth of the 20th Century, "[Keaton] was ahead of his time in many ways". It is exactly this prescience and timelessness that makes Buster Keaton a figure ripe for reference in contemporary performance. His type of minimalism, stoicism and lyricism transcended the 20th Century, and can be seen on-screen now perhaps more than ever.

Stevens cites Keaton's "self-contained stillness" as his "secret weapon", and we can see its weaponisation in the opening sequence of The Cameraman (1928) in which Buster aspires to be a newsreel cameraman in order to impress a girl. As an excited crowd gathers, yelling and gesticulating, to celebrate and capture the marriage of two famous individuals, Buster is caught in the melee and squashed against the woman who will claim his heart. He is a picture of enraptured calm amid the clamour.

That calmness or stoicism, despite deep inner turmoil, is something that can also be located in Oscar Isaac's critically-acclaimed performance in Inside Llewyn Davis (2013). Speaking to Scott Feinberg on the Awards Chatter podcast, Isaac reveals that the starting point for his singer-songwriter character Llewyn in The Coen Brothers' folk music odyssey was indeed Buster Keaton. "I thought that was a great inspiration for me", says Isaac, who wanted to tap into what he calls a "comedy of resilience" and to adopt a facial expression that "doesn't really change but has a melancholy to it". And so Isaac subtracted smiling from his arsenal of expressions to birth a character who is frustrated with the world and everyone in it.

But stillness isn't blankness. As both Keaton and Isaac convey, a limited palette can still paint many colours. There is one scene in Inside Llewyn Davis during which Isaac's sardonic melancholia feels particularly Keatonesque – although the entire sequence where he carries a cat onto the subway, his face glazed in faint irritation, before having to lurch after said feline on a crowded carriage, could be a silent comedy – and that's the car ride with John Goodman's Roland Turner. Llewyn rides up front with beat poet and valet Johnny Five (Garret Hedlund) and Goodman's cocky, cane-toting jazz musician reclines in the backseat. Upon snoring himself awake he begins to prod Llewyn with both questions and cane. When he discovers that Llewyn is a Welsh name, and launches into a long and uninteresting story, Isaac's face remains placid. But there is a perceptible smirk, a lick of the lips and a glance out the window that says: "this guy is unbelievable". Down the road and more deeply exasperated, Llewyn reveals that he's a solo act "now" because his partner Mike "threw himself off the George Washington Bridge". There is barely a glimmer of grief, just a stony stare into the middle distance as Isaac's big brown eyes concentrate on the road ahead, but still betray the sadness within.

That stare undeniably shares heritage with Keaton. In the book The Look of Buster Keaton, French film critic Robert Benayoun offers a series of insightful essays alongside strikingly rendered images of Keaton's face, in which his solemnity is on full display. Benayoun posits that "the aim of every close-up" in a Keaton film was to "confront us with [his] gaze. When Buster stares at some unexpected obstacle, in the offscreen space overhead, his gaze makes that obstacle, surprise or danger, or marvel visible… Keaton was the comedian of deliberate attention, intense and dynamic reflection; we can see him thinking" – just as we can see Llewyn contemplating Mike in that car.

Isaac isn't alone in exhibiting this trend towards minimalist acting, or what Shonni Enelow, an academic and author called "recessive aesthetics" in a 2016 article for Film Comment. Compared to Method performances, which functioned within a framework of "tension and release" and generated performances that were "feverish, agitated [and] on the edge of eruption", a remote performance is marked by tiny expressions, contained intensity and "a refusal of big reactions or loud moments". Enelow points to Jennifer Lawrence in Winter's Bone, Rooney Mara in Carol and Michael B Jordan in Fruitvale Station, and offers up a reading of their "emotional withdrawal in these performances as a response to a violent or chaotic environment".

Keaton might have done it for laughs more than integrity, but he too saw the value in responding to unpredictable and dangerous events with a stoic shrug or exhalation. This minimalism is also surely part of the reason he's endured. Critic and film historian Imogen Sara Smith points out that "the coolness and subtlety of his style [is] very cinematic in terms of recognising that the camera can pick up very, very small effects". That contemporary acting has become much more internalised and naturalised could be "the reason why he translates more [than other stars of his era] in terms of style of performance", posits Smith.

This recessive melancholy is equally visible in Awkwafina's performance in Lulu Wang's 2019 tragicomedy The Farewell. As The New Yorker observed, "[Awkwafina] gives a master class in hangdoggery", as Chinese-born, US-raised Billi, who returns to Changchun after discovering that her grandma Nai-Nai has weeks to live. After Billi's family decide not to tell Nai-Nai she's dying, she is forced into a mode of repression. The contrivance of that composure can be seen in the fact that prior to and upon learning of Nai-Nai's fate she is humorous, sassy and indignant. The shock of this news is etched all over her face, which doesn't go unnoticed by her mother: "Look at you, you can't hide your emotions". For the sake of her grandma, she learns how. As such, it differs from Keaton and Isaac's mode of performance which is grounded in immutability.

However, Billi's alienation in a culture that is both hers and not hers chimes with the way Keaton is often seen to be performing social conventions. Billi's Uncle Haibin explains, "We're not telling Nai-Nai because it's our duty to carry this emotional burden for her", and he chastises Billi and her father's westernised desire to tell the truth. Billi finds herself having to adapt to eastern values, no matter how uncomfortable they make her. Likewise, Keaton frequently played into the "innocent abroad" archetype; naive in the ways of life and love. In Sherlock Jr (1924) he studies a manual How To Be a Detective, shadows a man and in doing so replicates his walk, and finally, when he gets a moment alone with his love interest in the projection room of a cinema, must look towards the actors on screen to figure out how to kiss her. There is an awareness of performance in Keaton's persona and Sherlock Jr is just one instance where you see him modifying it according to what might be expected of him.

Similarly, Awkwafina moves between performance styles according to what is required of Billi, and there are moments of emotional release where she pivots into Method acting, as when Billi admits to her mother that as a child she was often "confused and scared because [her parents] never told [her] what was going on". But then she recedes and gives herself over to "hangdoggery". Keaton too gave a masterclass in that.

A less disputed element of Keaton's performance style was his sheer athleticism or what Stevens describes as his "signature kineticism". Which brings me on to Adam Driver. I could point to his thoughtful repose in Paterson, his slapstick humour in Marriage Story or his deadpan delivery in The Dead Don't Die as indicative of a Keaton-ness. However it was in last year's macabre rock opera Annette, directed by Leos Carax, that Driver demonstrated a "full-bodied enthusiasm and physicality", as Little White Lies' Hannah Strong put it, that more forcefully summoned the spirit of Keaton.

That skittish, unpredictable physicality is first apparent in Driver's Henry McHenry, an aggressively macho comedian with a reputation for "mildly offensive" jokes, when he stalks on to stage (having just eaten a banana) to rapturous applause. Before long he has burst into song and is leaping and frolicking about with what IndieWire called "balletic precision", in a manner that resembles both Denis Lavant in Mauvais Sang (1986) and Keaton in Grand Slam Opera (a low-budget short he co-wrote and starred in for Educational Pictures in 1936).

Lucidity and precision

"The other thing that's really distinctive about [Keaton]," explains Smith, "is this lucidity and precision". Although he was not a formally trained dancer, his acrobatics are full of the kind of rigour, lyricism and rhythm that any dancer would kill for. "Every little movement that he makes with his face or his body is very clear, but in a way that doesn't feel mechanical," continues Smith. "He had incredible control over everything he did." It is unsurprising then, that there are several actor-dancers (including Lavant) who also simulate Keaton with their level of control.

The first person who comes to mind is Miranda July, who The New Yorker once described as having "the steely fragility of Buster Keaton", and who performs an abstract dance sequence in her 2011 sophomore feature The Future. The performance – made up of precise and sometimes melancholic bodily contortions – shares a lineage with the American dance company Pilobolus (I cannot claim to be the first to notice this) who take their name from a fungus that "propels itself with extraordinary strength, speed and accuracy".

The second person is Ariane Labed, a Greek-French actress for whom dance is a recurring feature: she was cast as a synchronised swimmer in the 2020 TV series Trigonometry, had the best moves in The Lobster's silent disco, and schools us in the art of synchronised gesture during Attenberg's semi-dance sequences. The director of the latter film, Athina Rachel Tsangari, unsurprisingly singled Keaton out, in an interview with Culture Whisper, as an inspiring "composer of human movement".

In Annette, there is a pivotal scene onboard a ship in which the narrative reaches an emotional crescendo. There is a storm brewing, and a drunken Henry (Driver) attempts to waltz with his wife Ann (played by Marion Cotillard) across the stern. Driver's body now mirrors Keaton's in its perpetual motion. Despite their difference in stature they are both industrious and powerful, and more than just the specificity of their movement, its effect is such that you are never quite sure what will happen next, or what they're capable of. Moreover, they exert their physicality in a way that displays a tendency towards possessiveness and machismo. In The Cameraman (1928), Keaton kicks another man into a swimming pool for talking to his date. This anticipates a scene in which Henry wrestles a man known only as The Accompanist into his pool, having had suspicions that he posed a threat to the titular baby Annette.

The other aspect of physicality that Keaton and Driver share is their sex appeal. Returning to the words of Benayoun, he observes a sense of "the sublime in Keaton… He's glamorous. He's gorgeous. [He has a] sculptural sexiness". Not to gush too freely, but Driver is another such sublime specimen; a figure of extreme masculinity and muscularity. And what could be more glamorous than Henry McHenry riding his motorcycle, before kissing Ann with his helmet still on? Keaton and Driver have a commanding presence in common, and when they are on screen, you simply cannot take your eyes off them.

Keaton's performance style is known for its deadpan execution. No matter the ridiculousness of the gag – he liked a banana skin as much as any comedian – his face remains a picture of steadfast seriousness. As Smith points out, it is this contrast between his "deadpan serenity [and] his body constantly [being] subjected to all these indignities [that is] the essence of him as a performer".

Filmmaker and comedian Richard Ayoade frequently channels Keatons deadpan-ness, and often cites him as a point of reference when working with actors. In a 2014 interview, Ayoade reveals that he had Jesse Eisenberg watch Buster Keaton's films before starring in his sophomore feature The Double, feeling that they could demonstrate a "sense of someone acknowledging that everything bad that happens to them shouldn't come as a surprise".

Deadpan delivery and that lack of surprise are also notable in Donald Glover's acting. In Atlanta, the Emmy-winning comedy TV series about two cousins trying to work their way up in Georgia's music industry, Glover (who created and co-writes the show) stars as Earn Marks, an aspiring talent manager who approaches life with a stone-cold sobriety. "Van's dating other people, she's going to kick me out of the house [and] I'm also broke," sighs Earn in the pilot episode, as he explains his current situation with his baby's mother to a colleague, with a subdued weariness.

Earn's expressionlessness doesn't mean that he's devoid of emotion; when he hears his cousin Paper Boi's new track on the radio – having got it into the hands of a producer – he breaks out into a genuine smile. Rather, it serves to underscore the absurdity of modern existence. He is no longer outraged or surprised when setbacks come his way. In the pilot, the biggest reaction he can muster when a white acquaintance drops "the n word" twice in conversation is mild offence. No matter what happens, be it a man on a bus feeding Earn a nutella sandwich or a pet alligator strolling out of his Uncle Willy's house, there is a level of apathy to Earn's deadpan response because on some level, he's seen it all before. And like Keaton, he's just trying to survive.

Keaton's films have likewise been considered a response to the absurdity of modern existence. His characters endlessly invite and contend with calamity, existing in a world where structures – both mechanical and architectural – are in a constant state of precarity, and where the elements themselves (he is perpetually battling wind and rain) have turned against him. In the 1920 two-reel comedy One Week, Keaton and his new wife attempt to build a DIY house. They fail miserably. As Dana Stevens notes in Camera Man, "the resulting structure makes the cabinet of Dr Caligari look Grecian in its symmetry". After a freight train crashes through the building, they stick a "For Sale" sign in the rubble, and head for new pastures. You could just as easily see Keaton describing this character as homeless but "not real homeless" as when Earn defends his peripatetic living situation.

That said, there are of course other authors of this deadpan mode of expression who may well have influenced performers such as Glover. As Tina Post – an assistant professor at the University of Chicago specialising in racial performativity and deadpan aesthetics – asserts "the term [deadpan] precedes Buster Keaton or is coterminous with his rise". Post also points out that "the way that Keaton couples a blank expression with a bodily endurability is very much in line with American constructions of blackness." Post is quick to point out that expanding the definition or lineage of deadpan isn't a condemnation of Keaton himself, but rather a consideration of "the ways performatives move through American culture". Much as in the way the 20th Century's benighted use of blackface has evolved to allow for its memorable subversion, or rather inversion, in the Teddy Perkins episode of Atlanta.

This chimes with the way Keaton himself has migrated through screen culture, ever accessible and influential, with aspects of his performance style being adopted, reacted to and modified in order to suit a range of bodies, genres and purposes. There is still no-one quite like Keaton: the tension and contradiction in his comedy is as unique now as it was in the 1920s. However, it feels safe to say that the restraint as well as the commitment present in these acclaimed, 21st-Century performances owe a debt to a filmmaker and performer who figured out not just how to take a camera apart and put it back together again, but what it was capable of capturing and expressing.

Source: BBC